Herring fish lived in vast quantities in the waters around Scotland and was a relatively easy catch. It is known from 1550 that James V of Scotland encouraged fishermen from Fife to fish for herring around the Hebrides. These fish were caught in nets out at sea. Dutch fishermen also came to the Scottish waters for the herring and taught local people methods of fishing and curing. Herring, because it is so rich in fat with the oils spread throughout the body of the fish, needs to be used or cured and packed quickly otherwise it will go rotten in just a day. It was really the Dutch who fished the majority of herring until the eighteenth century.

Herring was first transported to Ireland and the West Indian plantations but later it was in great demand from Germany, Eastern Europe and Russia as a delicacy. Bounties by the British government helped the fishing industry expand with bigger boats and to increase production with barrel bounties. In the early nineteenth century the British government gave bounties on herring sold abroad. Once the railroad network was extended, the herring catch could be sold around Britain easily too. The Scottish fishing industry became the biggest in the world. 10,000 boats were in the industry in 1913.

The herring boats followed the shoals of herring round from the north west coasts from May round the north of Scotland, down the east coast and then on to the coast of east England in the autumn. Because of the necessity of packing the fish quickly the boats went out and came back every day.

The herring boats followed the shoals of herring round from the north west coasts from May round the north of Scotland, down the east coast and then on to the coast of east England in the autumn. Because of the necessity of packing the fish quickly the boats went out and came back every day.

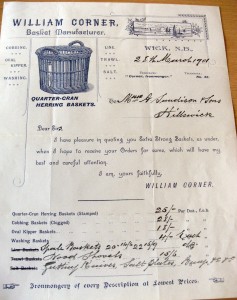

Baskets were a very important part of this industry. From the nineteenth century the catch was measured in crans which was approximately 1000 herring. The quarter cran basket was used both to land the catch and measure the haul. These baskets continued to be used until 1940 when boxes were brought in.

The Herring Girls

Baskets were also used at the port to process the catch. The fish were emptied into long wooden troughs called farlans. Teams of women would gut and sort the herring into baskets or small barrels. The fish were sorted for size and condition. The guts sold for fertiliser. It appears from the photographs that the baskets used were mainly oak swills/swales but some could have been made of willow. It is likely that the oak swills would have lasted longer than willow under such conditions.

Each team would consist of three women, two gutters and one packer. The packer was in charge and a curer would engage a team for each boat. Packing the fish in salt was the only way to preserve it for its long journey east. Gutters would gut the fish in one stroke of the knife, often able to gut one per second. They would often wind cotton material around their fingers to protect themselves from cuts and the corrosive brine. The packer would take the basket of gutted fish and tip them into a tub with salt. Then they were packed into the barrels in a spiral with all the tails to the middle then the next layer had the heads in the middle, and with a generous cover of salt to each layer. Each barrel would hold a cran.

Women were also the processers for the herring that became kippers. Baskets were used for the different stages. Again they would gut the fish this time putting them into an oval ‘cobbing’ basket or cob ‘mound’. This basket would be beside the worker as she stood gutting. Then she would wash them in running water in specific washing baskets or washing’mounds’ and transfer them into oval kipper baskets. These would then go into the pickle vats which were a mix of brine and orange dye for an hour. The fish would then be opened out and smoked.

Working on these gutting crews gave women untold new freedom to travel and work. In 1913, 2,400 women left Stornoway in May and June to go to the herring ports of Shetland and the East Coast. 1,613 of these women continued down to Yarmouth and Lowestoft. Some of these women stayed on in the towns to become domestic servants and some married and stayed in these new areas. Then sisters or cousins might find work through them, continuing the emigration of women from the far off isles and coastal ports of Scotland. Their independence and confidence shows in a strike they organised for a week in Yarmouth for more pay. 6,000 women were on strike. Even in 1938 there were 1000 women working gutting, packing and kippering in Stornoway. The crews travelled and lived together in huts with quite a lot of women sharing accommodation or in lodgings, at each port for the whole season. They had to take their own bedclothes, pans and dishes. The money earned by each crew depended mostly on their speed and skill. They were paid a small sum as a pledge of engaging them at the start of the season and then they were paid per barrel packed.

The baskets used by these women represented time and money to them. Each filled basket was one less to do in their day, and one more to fill each barrel that brought their wage. They must have been so relieved at the end of the day to see the last basket of fish disappear into the barrel.

Mary MacDonald from Point, Lewis was a herring girl in the 1930s. She said “I saw a lot of the world. I went to Lerwick, Stonsay, Lochmaddy, Yarmouth, Lowestoft, Peterhead and Fraserburgh.

Herring girls or fisher lassies started this work at sixteen years old, often following in the footsteps of relatives and being taught by them. These women worked a six day week and often for 12-15 hours a day. They would start when the first catch came in which could be at 5am. Because of the nature of the fish the processing had to be quick so often the women did not stop, only having a snack or mug of tea where they were.

As late as the 1960s women from Shetland were still working the herring in East Anglia.

So where did all these baskets come from? It would seem that they were brought to the processing ports from basketworks. The quarter crans would not have been made in Stornoway or Lerwick for instance. These were made in vast quantities in East Anglia but also there were basketworks around Scotland including Wick, Dundee, Montrose, Aberdeen, Leith and Skye. These had to be inspected by the Fisheries Board and stamped to insure that the correct measure was maintained. See the article on quarter crans here. The oak swills/swales may have been made at these basketworks but so far we have no direct evidence of that. It could be that they were imported. Some swales were made by travellers but many would have come from Furness in the Lakes. See the article on woven split wood basketry here. The Wick basketworks invoice here shows him offering on the left hand side at the top all the baskets for the kippering process ‘Cobbing’, ‘Oval kippers’ and ‘Washing’ and presumably these were made there to order.

By Dawn Susan

See Linda Fitzpatrick’s article on Scottish fishing baskets here

Resources

‘The Herring Girls in Stornoway’ Stornoway Amentiy Trust 2006

Dorothy Wright ‘The Complete book of Baskets and Basketry’

http://www.scotfishmuseum.org/the-herring-boom Accessed 14/12/2013

http://www.ambaile.org.uk/en/item/item_photograph.jsp?item_id=22070 Accessed 14/12/2013